My Tree of Life

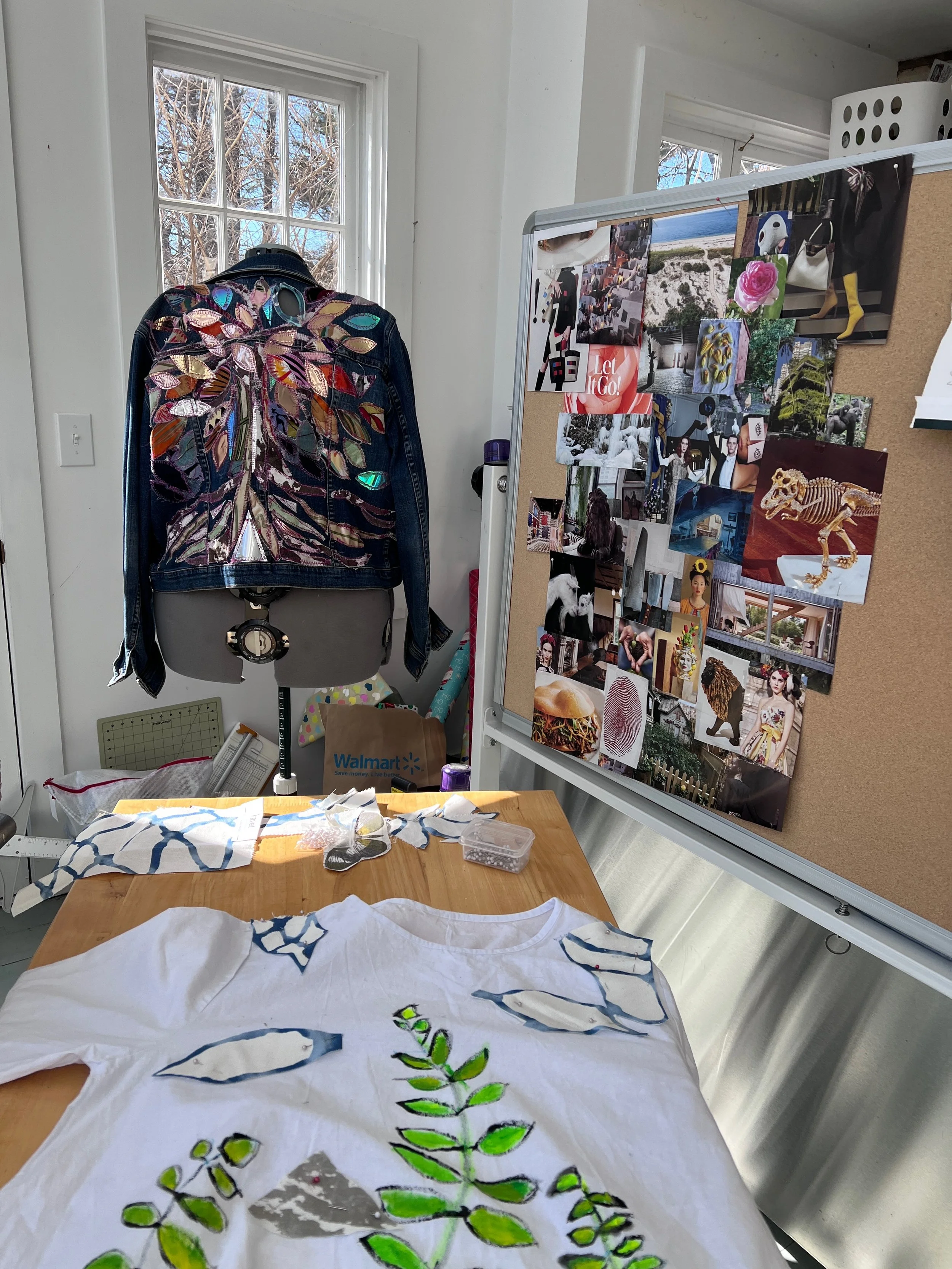

Sketch of the Tree of Life jacket in progress in the Dollhouse.

As a Vassar student drilling glass, playing with metal, and telling personal stories through abstract constructions in my art studio, I was metamorphosing my way out of an old self into a new one—re-spinning negative thoughts through an alchemic process into strong, fragile, defiant, glorious statements. Exorcisms.

I had an instinct that I’d return to making later in life. It started this spring with a jacket—though in truth, it began months earlier when I committed to Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, decades after my student days in art and architecture.

The jacket was a classic denim one, plain and worn—the kind I’ve had since I was a girl. I transformed it into something more charged: part experiment, part reclamation. After years of thinking in drawings, plans, and presentations for clients, I felt the pull to make things that were personal and tangible again.

I opened bags of hand-selected fabric samples from renovating my house—fabrics I loved but that had never found a home. It’s a particular kind of love: the love of patterns and textures and colors that elicit emotion simply by existing. I started making—not sure what I was making, but sure that I should be. I pinned and unpinned, cut and clipped, incorporated opalescent vinyl, colored threads, a bit of copper. Sitting at my sewing machine felt like opening a window I hadn’t realized was closed.

I collaged scraps of salvaged fabric, bits of forgotten embroidery, fragments of old sketches—creating what became my Tree of Life jacket. It wasn’t planned. It unfolded the way nature does: irregular, layered, alive. As I worked, I realized it wasn’t just about the jacket. It was about returning to who I’ve always been—a maker—but also who I’ve become: a designer of life.

When I find that maker groove, it’s meditational and rhythmic, like gardening. I lose myself while becoming something else. There’s always a feeling I need the piece to exude—that’s what guides me. I’m usually listening to music, and the process helps me dissolve my physical self, becoming one with nature. Time slips. I pin and stitch like an elfin bandit.

The Tree of Life feels like my origin superhero symbol. As a kid, I was curious about roots, dirt, the underworld—the creatures that move through the soil: worms, salamanders, nymphs, grubs—finding nourishment in a clay-like substance that seemed tough and unforgiving. I imagined trees were symmetrical, with their doppelgängers growing upside down beneath the surface.

Tree of Life mosaic, master bath renovation — a quiet echo of the same pattern stitched into the jacket.

Throughout my Victorian house in upstate New York, I’ve added several Tree of Life mosaics as tributes: to the house, the place, myself, to nature, to the Hudson River painters like Frederick Church and Thomas Cole who once inhabited this valley—and to the Mohicans who lived on this land long before them.

Sometimes, transformation doesn’t look like reinvention.

It looks like remembering.

Interpolation: jacket photograph → hand sketch.

The finished Tree of Life jacket — a collage of fragments, stories, and light.