The House That Taught Me the Truth in Contradictions

The UFO Years. The light was real. and I believed truly that I had been chosen.

When I was a Studio Leader at Rockwell Group, I tried to lead with empathy. Twenty people, twenty temperaments, and a belief that if I cared enough, they’d thrive. Some did. Some mistook empathy for permission. I learned that compassion without boundaries can warp just as quickly as authority without heart.

Maybe that awareness began decades earlier—in a house that was already a contradiction.

Where the Walls Were Listening

The view from my childhood bedroom window to the front door in Wilton, CT.

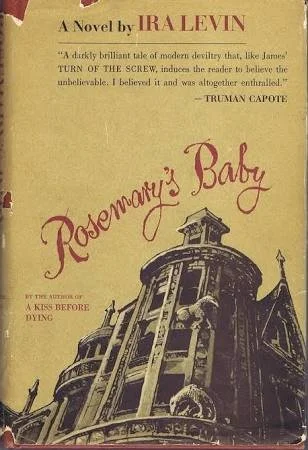

The house in Wilton wasn’t exactly Victorian—more a cottage grafted to a chicken coop, with additions tacked on over a hundred years until it became a U-shaped sprawl with three front doors and too many ways out. It had once belonged to Ira Levin, who wrote Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives there.

In a 2007 letter to the editor of The New York Times, Levin confirmed that Wilton was the model for Stepford—a fact that electrified the town’s gossip circuit long before I learned to spell “suburbia.” My bedroom was said to have been his writing studio, which may explain why I always felt the walls were listening.

Local hearsay said he’d had the place exorcised. The proof—or the receipts—are still there: jagged holes cut into the backs of kitchen and living-room cabinets to “release the spirits.” Maybe there’s a rational explanation, but I like the version where the ghosts needed an exit strategy.

That first night, Labor Day weekend 1982, a heavy counterweighted window slammed shut with a bang that split the air. My parents came running, smiling the way adults smile when they’re scared too. I was in fifth grade and already attuned to atmospheres—drafts, creaks, the temperature of fear.

That house made me. I loved its wrongness, its rambling plan, the way the original front door now faced the backyard like it had turned away from polite society. It was the opposite of the new suburban castles rising around us: homes without history, all drywall and whirlpools, no ghosts allowed.

Learning to See from the Outside

During those years, I often felt myself float up, watching from the ceiling while my body performed the script of a well-behaved girl. I learned empathy as surveillance—studying how people expected you to act while knowing you were something else entirely. That split never fully closed; it just became useful later when I managed teams or clients.

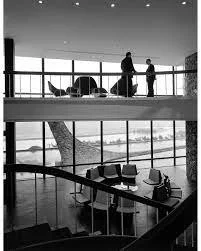

Half the fathers in town worked at IBM. When I visited, everything felt impersonal, calibrated. Later I learned it was designed by SOM with courtyards by Noguchi—architecture I respect deeply now. Back then it only confirmed what I already sensed: some buildings serve efficiency; others hold the mess of being human. Both are necessary. It took me years to see that.

From Gehry to Rockwell, and Back to Myself

At Gehry Partners, I learned devotion—the kind that keeps you in the studio for a hundred hours a week, chasing form until dawn. That brutality gave me craft, endurance, an appetite for complexity.

Rockwell was a different tempo: faster, shinier, more interior, more ephemeral. Gehry builds for the century; Rockwell designs for the season—and both are valid. Rockwell taught me to enjoy the intimacy of interior architecture, to see hospitality as a kind of stagecraft where design sets the scene for life to unfold. Reconciling those two worlds forced me to question the capital-A architecture values I’d carried from Yale and Gehry, and to find my own definition of what’s lasting.

After cancer, after leaving the Guggenheim, returning to that pace felt like re-entry into life itself. Making things—gardens, drawings, experiments—was a way to prove I was still here, still capable of growth. The impulse to build and nurture never really left; it just changed form.

The UFO Years

For several years, I saw a UFO every night from one of my bedroom windows in Wilton — descending straight down in silence between the trees. I believed, truly, that I’d been chosen, that I was being watched. That conviction carried me through new schools and small-town gossip. I had proof, nightly.

One evening, my mother came in mid-landing. She called my dad. He arrived with a map, traced a line west, and showed me how the house sat directly in line with a landing strip at Westchester Airport.

My UFO was an airplane.

The light was real. The story was not.

I remember the shame of losing my miracle, the hollow where specialness had lived. But also the wonder that lingered—the way logic didn’t erase awe, just reframed it.

Living with Contradictions

A building can be haunted and functional.

A mentor can be visionary and impossible.

A leader can be gentle and still demand excellence.

A child can see a UFO that is also an airplane.

I’ve learned that contradictions aren’t the exception; they’re the landscape. The work now is navigating them without needing resolution—staying curious in the tension between wonder and fact, ego and empathy, permanence and change.

It’s a hard world to read cleanly, but probably that’s the point.

Life, like design, happens in the blur.